Quick summary:

"The Money" begins where "The Dolls" ends: with Elena and Lila outside Don Achille's (Antonio Pennarella) door, steeling themselves for a confrontation. Predictably, this middle-aged mobster is clueless about their dolls and sends them away with a wad of condolence cash, which they eventually use to buy "Little Women" (1868). Louisa May Alcott's words inspire fantasies of writing a book together that will catapult them out of the neighborhood to echelons of fame and fortune. When Lila's father, Fernando (Antonio Buonanno), forbids her from taking the middle school admissions test, he not only curtails her potential but causes her first minor rift with Lenù, who is allowed to continue studying. At the end of the episode, Don Achille is murdered and Alfredo Peluso (Gennaro Canonico), obviously a scapegoat, is arrested for the crime.

Corresponding book chapters:

Some scenes happen earlier in the novel, but "The Money" mostly covers Chapters 14-18 (through the end of the Childhood section).

Notable choice (complimentary):

After Lenù is caught skipping school, she returns home and gets the shit beat out of her by her father (Luca Gallone). In the book, this scene is a passing bit of commonplace violence that doesn't stand out. Onscreen, it becomes the perfect illustration of internalized misogyny and toxic masculinity. Here's how Ferrante describes it:

At night my mother reported everything to my father and compelled him to beat me. He was irritated; he didn't want to, and they ended up fighting. First he hit her, then, angry at himself, he gave me a beating.

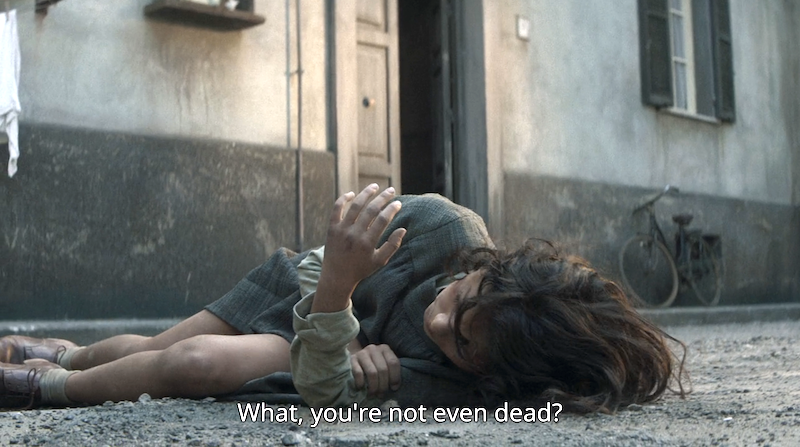

In the show, Immacolata (Annarita Vitolo) goads Vittorio by diminishing his masculinity. She hisses, "You don't even know how to hit your daughter. What kind of a man are you?" In response, he slaps her across the face before roaring into Elena's room with a theatrical ferocity and hitting her while screaming, "Is that enough for you?" The most horrifying part is when he turns away from Elena, now cowering in a heap by the window, faces his wife, and snarls, "She's going to school. She's going!" Nothing sucks more than watching a woman reinforce the patriarchal standards that oppress her.

When Vittorio exits the room, Immacolata stands still for a beat as a range of emotions cross her face: fear, regret, jealousy, resentment. She holds it all together in front of Lenù, but we see a hint of her inner emotional life... just enough to show that there's unspoken complexity to her actions.

Notable choice (derogatory):

Elena is so much cuntier in the novel and I wish we got to see that side of her in the adaptation. Even as a child, she's constantly propping herself up, desperate for Lila to recognize her accomplishments. Her own insecurities drive her to pour salt in Lila's wounds, gunning for a feeling of superiority that she doesn't deserve and will never truly achieve. Ferrante writes,

As soon as I could, cautiously, [...] I found a way to remind her that I had gotten a better report card. As soon as I could, cautiously, I pointed out to her that I would go to middle school and she would not. To not be second, to outdo her, for the first time seemed to me a success.

TV Elena as more of a passive victim and less of an active antagonist within the friendship. In the novels, her flaws are blatantly on display and I often find her very unlikable in a realistic way. Take, for example, all the times she wishes for Lila's death. I'd be lying if I said I didn't respect this horrible honestly. TV Elena's ugliness is subdued and as a result, I occasionally find her lacking. I like her best when she's just as mean as Lila, only in a bookish, introverted way.

Thoughts:

Once Elena and Lila's friendship is cemented through the business of the dolls (whose whereabouts remain unknown), they settle into a love/hate dynamic that persists for years to come. Both girls dream of escaping poverty by writing a book and becoming rich a la Jo March/Louisa May Alcott, but it quickly becomes obvious that only Elena will be afforded this opportunity. It's a tale as old as time: luck changes one person's trajectory while another, who is just as — if not more —deserving, needlessly suffers. Everything that follows in this sprawling, decades-long story harkens back to this senseless inequality.

Oh, to be an excited young bibliophile discovering how fun it is to read a book until it disintegrates.

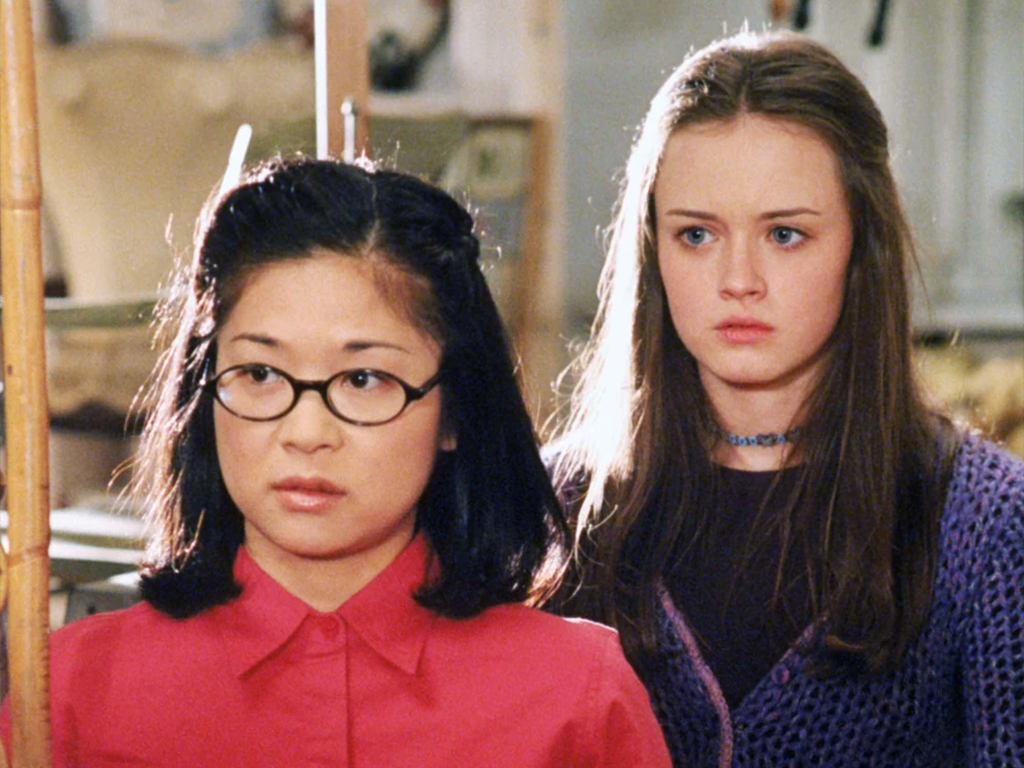

From an early age, Lila possesses a fearless confidence that impresses Elena. She forges ahead immediately without waiting for instructions on what to do and how to do it because she believes in her own intelligence. She writes/illustrates "The Blue Fairy" and fights back when her parents (successfully) bar her from attending middle school. Imagine what she could do with a young adulthood devoted to education instead of the daily struggle to survive. Elena is Lila's foil. She's cautious and timid, hesitant to proceed without constant reinforcement. If her parents told her she wasn't allowed to go to school, she probably would have said, "Okay." These differences manifest in an early conversation inspired by "Little Women":

Lila: Jo also wrote a story and no one thought she could write it. We have to do the same thing.

Elena: Yes, even though Jo's a grown-up and we're not.

Lila: You want to grow old and then make money? We have a pail here in our head, full of words, where there's everything we need. You pull out one word, then another, and that's how we'll write the book.

Elena: Maybe we should first go to the school where you study Latin.

Lila can't wait to learn more before writing her story; if she doesn't do it now, it will never happen. She knows how unlikely it is that she'll ever formally study Latin. Despite her assurances that she'll find a way to attend school without parental approval or money, doubt grows over time. In the scene that follows, the girls run into Gigliola (Alice D'Antonio), who has just been given the green light for the admissions test, and as they pass the grocery store, they hear the Carraccis bragging about Alfonso's scholastic prowess. If these two yokels are moving forward with school, it's possible Lenù is next and if so, where does that leave Lila? She can't even bring "Little Women" into her house lest her father discover it.

Back at their respective apartments, Lila's fears become reality. Both girls are berated for their school ambitions, but the Grecos relent while the Carraccis stand firm. As fights rage on in the background, the girls observe one another with forlorn expressions from their windows. Their faces are initially shown in closeup, but the last image of Lila is shot from afar, making her look even smaller than she is. It's all over when Vittorio proclaims that as long as Lenù is "the best of all," she can go to school. In a moment that dictates the rest of their lives, Lenù is placed on a path to upward mobility, whereas Lila is condemned to hardship.

In the book, these scenes with each family are brief and they happen earlier in the narrative, before the trek to Don Achille's. This expansion of them serves the story well, engendering empathy for Lila before her attempted seaside sabotage. Another scene that serves a similar purpose is the one between Nunzia and Maestra Oliviero (Dora Romano). Maestra praises Lila profusely, trying every tactic she can think of to persuade Nunzia, but nothing works. Fernando has already made a decision and no one's opinion, especially not a woman's, will change his mind. There's no one left to advocate for Lila, so she'll have to take matters into her own hands.

Since Lila is powerless to shape her own future, she seizes control through Lenù. On their journey to the sea, Lenù walks ahead, carefree and excited for a new experience while Lila nervously looks at the ground, growing more visibly uncomfortable with each step. Similar to the book, Lila's decision to turn back early is ambiguous. Is her own fear of leaving the neighborhood giving her second thoughts or is it guilt over potentially ruining Elena's life? Either way, it's irrelevant. By the following day, Lenù understands the impetus behind Lila's plan but ultimately forgives her when nothing (beating aside) changes.

Lenù's forgiveness is also aided by the turn of events over the next few days. In class, Maestra tears Lila a new asshole for showing off, yelling, "You think you're the best, don't you? But you're nobody." Maybe her own youthful ambitions were similarly thwarted and this harshness toward Lila is actually a form of self-loathing? It's ambiguous, but this outburst combined with her "plebs" speech shows that she's no longer Lila's ally. She doesn't give a shit about "The Blue Fairy" and unless Lila takes the admissions test, she doesn't give a shit about her, either. All of this prompts Lila to quarrel with her father, who unceremoniously tosses her out the window, breaking her arm. In the show, all the neighborhood women rush to help and when they ask what happened, Nunzia says, "Nothing, she just fell." In the next scene, Lenù enters the kitchen for breakfast and the whole family (sans her stone cold bitch of a mother) applauds, congratulating her on passing her exams. One girl is punished for her aspirations while the other is fêted. Don't worry: this won't have lifelong ramifications.

Random observations:

- Conspicuously missing in the scene where Lila and Elena leave the neighborhood? The fat old man who whips out his penis. Naples and the NYC subway have more in common than I would have guessed.

- Elena, forever the little simp, tells neighborhood ogre Don Achille, "Good evening and enjoy your meal," before rushing off with the extorted money. Lila doesn't even look him in the eye.

- I hate all the men in this series, but it breaks my heart to see child Rino fight for a salary so that he can pay for Lila's school. (It's probably motivated by selfishness, but still).

- The circumstances surrounding Alfredo Peluso's arrest for Don Achille's murder are different in the book. I suspect they were changed because the child playing Carmela wasn't suitable for a larger role. I don't love the casting for Gigliola (one of my favorite side characters), either, but the most crucial thing was to get it right with Lila and Lenù, which they definitely did.

- Copper pots, mentioned for the first time in "The Money," are important throughout "My Brilliant Friend." Let's pour one out for all the professors reading undergrad essays about how they symbolize Lila's supernatural abilities and blah blah who gives a fuck [insert ChatGPT summary here].

- The man with a missing index finger (Vincenzo Merolla) isn't in the book; I'm guessing he was added to highlight Lila's astuteness regarding the neighborhood. She clocks him in "The Dolls" and then in this episode, notes his allegiance with Don Achille. Her observations are later proven correct when Finger Man gets his ass kicked outside the Bar Solara as punishment for Don Achille's wrongs.

- As Lila narrates her version of Don Achille's murder (using the pail of her mind), visuals alternate between her animated expressions, scenes of the neighborhood, and the most dramatic beats of her story. Yes, she's a child, but she's so damn persuasive that I would probably believe whatever she says, too.

- Ferrante describes Alfredo's arrest as "the most terrible thing we witnessed in the course of our childhood." Maybe Ferrante/Elena sees it that way in hindsight considering how the neighborhood politics evolve. As portrayed onscreen, I feel like Lila's broken arm is a significantly worse event. Yes, violence is unremarkable in the neighborhood, but how many parents actually murder their children? Fernando legitimately tried to kill her.