Vibe:

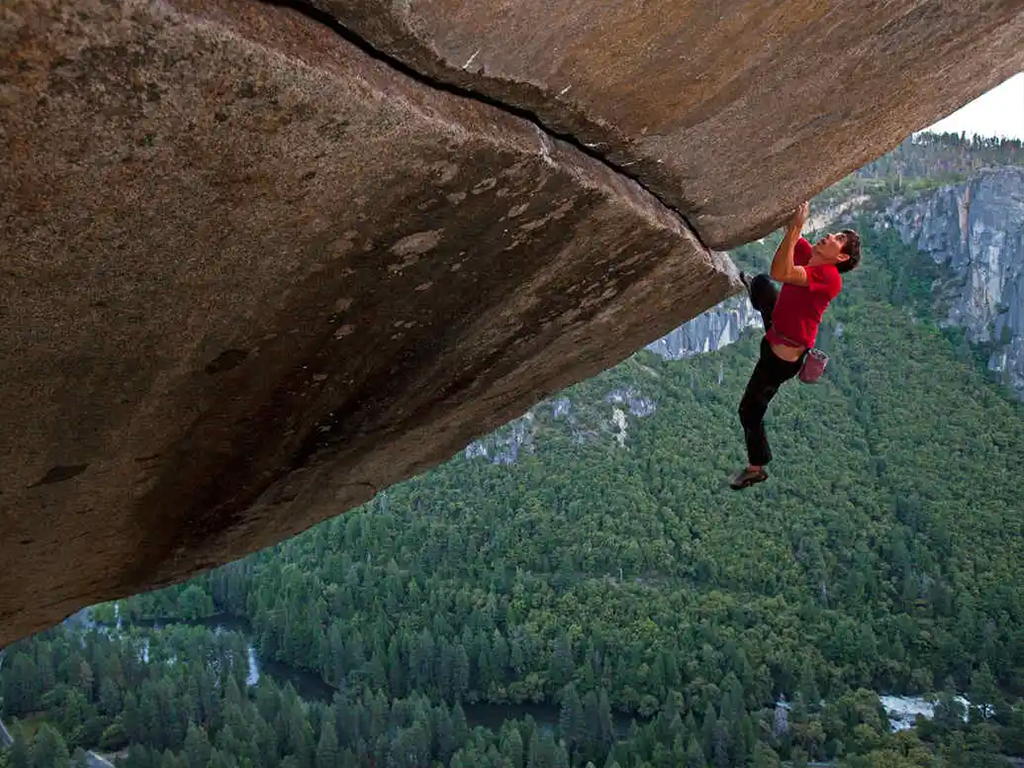

"Free Solo" is 1/4 celebration of a triumphant athletic endeavor, 3/4 examination of a man who is willing to put himself and all of his relationships at risk to achieve it. The action of the film took place in June 2017, so there's no ambiguity over whether or not Alex Honnold completes his goal. Anyone who follows climbing even tangentially would have heard about his free solo of Yosemite National Park's El Capitan.

Somehow, knowing that he survives doesn't make this movie any easier to watch. I wouldn't describe myself as someone who is especially afraid of heights, but watching Honnold dangling 2,000 feet in the air, only stabilized by two minuscule points of contact, was enough to make me feel queasy. Unless you're tough as nails, fully expect to spend the better part of 100 minutes with sweaty palms and a lurching stomach.

Best time to watch:

Watch this movie when you're dealing with a bout of laziness. The older I get, the more difficult it becomes for me to drag my ass outside for a run in the miserable cold of winter. If Honnold can free solo El Cap then immediately do a hang board workout, I can slog through 6 miles in light snow without complaining. Nothing gets me motivated like watching someone else accomplish something amazing. Sometimes the comparison makes me feel bad about myself, but it typically helps to reinvigorate good habits and put my situation into perspective.

Worst time to watch:

If you watch this movie on one of those tiny-ass airplane screens, we can no longer be friends. I recently noticed that it is now available on Delta flights but don't understand why anyone would want to watch it that way. See it on a big screen, if possible!

Where to watch:

"Free Solo" is streaming on Disney+.

Quick summary:

In this film, Alex Honnold trains to become the first person to ever free solo El Capitan's Freerider at Yosemite. At the same time, he navigates a new relationship, deals with countless questions about his own mortality, and struggles with his obligations to the people who care about him.

Thoughts:

Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi are a married couple who also happen to make films together (aka living the dream). Chin is a professional climber and skier who also got into photography and filmmaking over the years. He is a completely self-taught photographer whose work has been featured in publications like National Geographic and The New York Times Magazine. He's worked for huge companies like Apple and The North Face on commercial film projects and directed one previous documentary in 2015 (also with Vasarhelyi) called "Meru."

Vasarhelyi was a documentary filmmaker long before she met Chin. Her first film, "A Normal Life," came out in 2003 and won Best Documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival. Her second and third films, "Youssou Ndour: I Bring What I Love" and "Touba," did even better, winning multiple festival awards apiece. When she met Chin, he was beginning to work on "Meru" and asked for her help. From there, a true partnership was born.

Since Chin is an experienced climber, well-versed in adventure filmmaking, and friends with Honnold, he makes several appearances throughout "Free Solo" and becomes a key character. Vasarhelyi, a non-climber, is completely behind the scenes. Both this film and "Meru" could have easily been standard sports documentaries, chronicling men as they run down impossible dreams, but they evolve past this predictable trope. Outside Magazine says this about Vasarhelyi:

She helped break the mold of the typically bro-heavy genre of climber cinema and extreme-sports flicks in general. (See: the entire oeuvre of Warren Miller.) "Meru" delves into the fear and support that coexist in the families of these men. This, too, is largely thanks to Vasarhelyi’s influence.

The most interesting aspect of "Free Solo" is the why, not the what or the how. Why does Honnold feel compelled to pursue a sport that leaves zero room for error? Why is he willing to live a life that requires emotional disconnect in exchange for success? It's easy to gape in awe at his career and herald him as the pinnacle of extreme athletic prowess without going any further, but this documentary isn't interested in taking that route. Vasarhelyi and Chin recognize that Honnold isn't a typical person and their film works well because it spends a majority of the time trying to figure out why he's compelled to put his life on the line in the name of success.

I'm not a climber, but I've been casually following Honnold's career since his 2008 free solo of Zion's Moonlight Buttress. As someone who is interested in testing and pushing past supposed physical limitations (for me it's with running), I find him endlessly fascinating. I've never attempted to solely dedicate myself to a physical endeavor like Honnold, but I spend far too much time fantasizing about it.

I grew up reading books like John L. Parker Jr.'s "Once a Runner" (1978) and Chris Lear's "Running with the Buffaloes" (2000). I've long been obsessed with stories about men who take a "fuck it" approach to everything that isn't [insert passion here]. It's rare to hear about a woman who adopts this mentality, likely because we simply don't have the luxury or the social conditioning to even recognize it as an option ... but I digress. Filmmakers and writers are drawn to this type of person because they are rife with artistic potential. What's more interesting than a story about an extraordinary person who lives outside of social norms?

While the media has always portrayed Honnold as different and sometimes even superhuman, he's always come off as relatively happy and personable. "Free Solo" pushes past this simplified narrative and looks at some of the damage that drives his desire to do crazy shit that is unfathomable to most of us.

At one point, Honnold talks about teaching himself to hug at age 23. His family didn't show physical affection or say "I love you" when he was a kid. The Honnolds were ice fucking cold. My family wasn't quite this extreme, but I suffer from the same general damage. I wasn't explicitly told "good enough isn't," but it was heavily implied! No matter how successful or together I might look to an outside person, I always feel like a complete failure. Honnold says, "No matter how well I ever do at anything, it's not that good," and goes on to explain that "the bottomless pit of self-loathing" is what pushes him to solo. I wish this wasn't so relatable, but it is.

The difference between us is that my depression combines with self-loathing and gives me pause. I worry that if I get the thing I want and am still unhappy, that I'll never be happy. Maybe I've lost my capacity for happiness and this baseline "blah" that I feel most days is all there is for me. That thought is too dark to bear.

When Honnold goes in for an MRI, he fills out a questionnaire that asks if he's depressed. The camera cuts before he answers but we do hear him say, "hmm." I wouldn't be surprised if the answer was "yes." There are times when I think I would do almost anything just to feel an emotion. I wouldn't categorize myself as impulsive, but I would certainly take a calculated risk if the payoff was euphoria.

Although certainly extreme, Honnold's behavior kind of makes sense based on what we know about him. It becomes complicated and often questionable when a film crew and Sanni McCandless are added to the mix.

There are several moments during "Free Solo" where Chin wonders about the ethics of the filmmaking process. What if a member of the crew accidentally distracts Honnold and causes him to fall? Is it possible that the presence of cameras might create undue pressure, leading him to make decisions he normally wouldn't? These concerns are legitimate, and I can't say whether or not Chin made the right decision.

Honnold obviously wanted this film to be made ... whether for fame, money, or memento, who knows. If he didn't, he would have simply crept off and tackled El Cap without breathing a word of it to anybody. His willing participation alleviates some of the filmmakers' responsibility. Honnold is someone who assesses risk all the time; the fact that he trusts Chin and Vasarhelyi speaks volumes. I think the murkiest/toughest question is if those involved are emotionally equipped to deal with a potential tragedy lest the climb goes horribly wrong.

Mikey Schaefer could barely keep an eye on his viewfinder and is visibly uncomfortable during Honnold's solo. When it's all over he says, "I’m done – this is it. We don’t need to do this again." I'm not sure how he would have fared if Honnold hadn't succeeded. It doesn't do much good to worry about these factors now, though. Most of the people on the crew are climbers who, like Honnold, are capable of weighing risk against reward.

If you haven't already realized it, I'm of the "people should be able to do whatever the fuck they want within reason" mindset. If Honnold wants to risk his life for something he finds meaningful, who are we to try to stop him? An opinion piece in Outside Magazine surmises that the audience is just as culpable as the filmmakers:

By watching "Free Solo," by clicking Alex Honnold YouTube videos, by reading news stories, by going to his book signings, we create the market for the free-soloing content that gives Honnold sponsors and opportunities in the first place.

But ... is this bad? If Honnold were free soloing only because he felt it was crucial to maintain sponsors, I might say yes. Capitalism pushes people to make dangerous decisions out of necessity every single day. It's not unusual, but that doesn't mean it's easy to stomach. If free soloing makes Honnold feel alive and is what he enjoys doing most, then why shouldn't he let it kill him if that's how the cookie crumbles? Enter: McCandless, Honnold's girlfriend, a regular figure in the film who often suffers from the Skyler White problem.

Nothing McCandless says is unreasonable, but I found myself getting irritated with her because of the way she seemed to impede Honnold's progress. He is the protagonist, the person driving all of the action of the film, and as viewers, we are aligned with him and want to see his story come to a satisfying close. When he's with McCandless, he first suffers two compression fractures in his back (she lets the rope slip when they're climbing together) and then sprains his ankle (no one knows what happened there). Honnold says, "After it all happened, I wanted to break up with her. I was like, this is bad for my climbing."

For a second, I found myself shaking my head like, "Yeah, you probably should break up with her." Then I snapped out of it and thought, "Wait, no ... she should break up with you! You're the asshole in this equation." McCandless obviously cares deeply about Honnold, enough that she's willing to put up with his bemused shrugs in response to her declarations of love. She recognizes that he is emotionally damaged and working through some shit but remains supportive and understanding. All she asks is for him to begin factoring her in when he makes life-or-death decisions. It's not a huge ask! Quite frankly, if the relationship is something that Honnold values and wants to keep around, he needs to consider McCandless' wishes, too, not just his own.

I think the filmmakers are aware of how McCandless might be perceived, and they do a good job of backing her up with all of the other important people in Honnold's life. Tommy Caldwell and Peter Croft echo her sentiments and are actually more actively discouraging. McCandless takes an "I would prefer if you didn't" approach, whereas Honnold's friends are more direct about their desire for him to change his mind.

There is a constant reminder of mortality throughout the first 75 minutes of the film. Caldwell tells us, "Everybody who has made free soloing a big part of their life is dead now," and we're given a brief history of free soloing that proves his point. The fact that Honnold could die is never glossed over or downplayed.

The last 1/4 of the film is Honnold's climb of El Cap and the subsequent celebration of his efforts. Even then, we're still reminded that his success is propelled by a certain level of emotional repression, that it's not all superhero strength and admirable work ethic. When Honnold talks to McCandless after the climb, this is what he tells her (condensed for clarity):

"I'm sort of at risk of crying here too... I feel quite emotional. Don't cry San-san, it will make me cry. I think the movie would be better if I burst into tears, but I don't really want to. Well I do want to kind of, but..."

I cry over videos on the Internet that feature cats I've never even met before and this dude can't let himself shed a few happy tears after accomplishing something that he dreamed about for 8 years? That is the price you pay for this kind of success. What gives me hope is that at the end of his call with McCandless, he tells her that he loves her. Maybe, finally, Honnold has begun to let someone penetrate the armor that he's spent a lifetime carefully preserving.

Stray observations:

- Does Honnold own a fork or ...?

- "This sucks. I don't want to be here. I'm over it." - Me, five minutes into my work day, or Honnold before he bails on El Cap?

- Caldwell is a sardonic motherfucker whom I enjoy tremendously. After Honnold's successful climb, this is his compliment: "Good work not plummeting to your death." He wrote a piece about Honnold for Outside magazine that I recommend reading.

- I dated a dude in college who used to pee into Gatorade bottles because he didn't feel like walking to the bathroom down the hall. Spoiler alert: he is not the dude I married.

- I detest Tim McGraw's song "Gravity" and feel likewise "meh" about Marco Beltrami's score. After Nick Zammuto's work on "We the Animals" (Zagar, 2018), everything pales in comparison.

- David Sims' comment on Letterboxd kills me: "A great movie about how annoying it is to date men." I highly recommend flipping through the first two pages of "popular reviews" because they're all pretty funny.